Representation Matters. It’s a phrase tossed around in headlines and hashtags, but it’s worth far more than a moment’s righteous satisfaction. I could offer a laundry list of reasons why it’s important. For now, I’ll narrow it down to the most significant two.

- Self-Worth

When I was a little girl, I read hundreds of stories. Within those pages, I found characters with similar goals, ideals, personality traits, perspectives, emotions, and interests, yet most of them were boys. And, not a single one looked like me.

So, I wrote.

I wrote stories, where little girls excelled at sports and beat the boys…because I did. I wrote stories, where little girls were the smartest in their class…because I was. And my favorite of the stories I wrote was about a young she-wolf, who overthrew the patriarchy and led her pack to a better society.

I’m still working on that.

As exciting as these stories were for me, the sad reality was that despite tossing gender stereotypes to the wind, the concept of a white protagonist was so ingrained in me that my heroines, when human, were white. Even my characters didn’t look like me.

And, why would they? As young children, all of us are exposed to prejudiced attitudes. These attitudes—expressed repeatedly in books and other media—gradually distort children’s perceptions until negative stereotypes and myths about people outside of the majority are accepted as reality. By the time I started writing, I’d been exposed to thousands of words and images featuring white characters as protagonists, highlighting Caucasian features as good, attractive, and right.

Which meant what I saw in the mirror was bad, ugly, and wrong.

When I did finally find characters who resembled my wrong face—the nameless mulatto girl, seemingly referenced for no other reason than to prove the white protagonist was kind to servants—it was too late. My developing mind had already been taught, “The world isn’t built for you. You’re not normal. And, you’re only here to serve those who are.”

If this is the effect of merely my race not being represented in literature, consider the impact on the other intersections of my identity. What if, in addition to not being white enough, I’m also not straight enough? (I’m not.) What if I’m not young enough? (I’m not.) What if I’m not thin enough? (Are women ever?)

We read literature to learn about life, to immerse ourselves in stories and experience them as an insider. Being constantly cast as an outsider chips away at our sense of value.

And unfortunately, the adverse effects are not limited to those who are rendered invisible or reduced to stunted stereotypes. Even compassionate members of the majority, whose story and likeness are often part of the narrative, may not see how lack of fair representation negatively affects them, too.

Which brings me to…

- Perception

My experience querying agents with my first manuscript led to several unfortunate responses, not based on the quality of my story, but questioning the validity of my black characters. More specifically, “they did not sound authentically black.”

As if there is only one way to exist as a black person.

Countering this myth is part of what drives the Own Voices movement—the push in recent years to have more people telling their own stories. Yet when it comes to getting published, many underrepresented authors are shut out because the publishers say they already have “a black story” or “a gay story.”

In 2009, Chimamanda Adichie gave a Ted Talk called The Danger of a Single Story. In it, she states, “The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.”

This not only skews people’s perceptions, but can lead to dangerous prejudices that we don’t even recognize. Exposing readers to a wide variety of representations challenges stereotypes and other harmful preconceived notions about those who identify differently from them.

For example, there are innumerable ways for someone to live with a disability. Queerness is so multifaceted even people within the community lose track. And when you compare the lives of Stacey Abrams, Lenny Kravitz, Laverne Cox, Colin Kaepernick, and Meghan Markle, how can anyone believe there is only one black experience?

If we are to improve awareness for the intersections of underrepresentation in the world, we must make space for more stories outside the dominant narratives. And we as authors are uniquely qualified to blaze the trail toward more inclusive perspectives.

I offer three steps to help pave the way.

- Read more inclusively.

Seek out books written by and about people whose identities differ from yours. The more we learn about other communities, cultures, and perspectives, the more worldly and knowledgeable we are about ourselves and our own surroundings. That in turn will fuel your art and enrich the stories you tell.

- Write more inclusively.

Populate your stories with a cast of characters from a variety of backgrounds. When it comes to race, ethnicity, age, gender, gender identity, gender expression, religion, sexual orientation, ability, class, and economic status, we do not live in a homogenous society. If we are to be true to our art, the same should be true for our stories.

Let’s work toward writing inclusive books as a collective goal—books with diverse characters, books that challenge the dominant narratives, books that offer more accurate reflections of the real world. Over time, we can diminish that sense of otherness, disempowering it so that the next generation of readers will understand they were not only seen, they were valued.

- Share your stories.

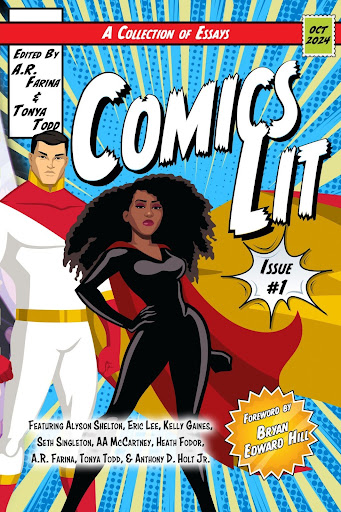

At a certain point, I recognized that if I wanted see more stories for me out there, it fell to me to write them. If I didn’t, who would? Now all my stories feature mixed black women (with cats, because ailurophiles deserve representation, too).

If you are an author from an underrepresented community, consider sharing the various nuances of your lived experience through your characters. Your stories don’t have to revolve around this underrepresented element. You can write a man in a wheelchair running for president. You can write a queer character whose biggest moment in life had nothing to do with coming out. You can build a world in any genre, using these qualities to create any type of character you want. An amputee assassin. A transgender trapezist. A Chinese cheesemonger. My idea of a great protagonist is a biracial vampire queen, but hey, to each his/her/their/eir own.