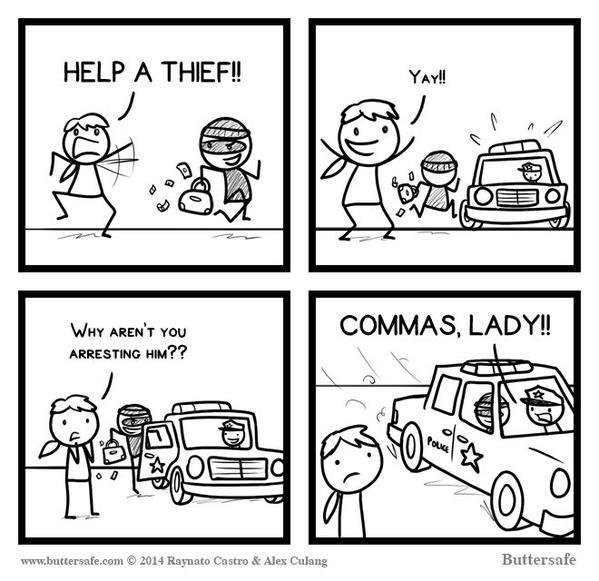

Woot! You made sure your story is ready to be shared with the world!

Except, is it really?

Think of it this way: your story is out of bed and dressed, drinking coffee and preparing to leave the house. But wait, do those shoes actually match, or is that a brown sandal and a black sandal? Maybe that hair could use a few more moments with a brush…

Taking the time to edit at this point saves everyone (especially your editor) a lot of time and energy. Let’s polish up that outfit and make sure everything is where it should be.

Disclaimer: you’re going to read your story AGAIN (I know, awful, right? Please, you know you love it. That’s why you wrote it!). Except this time, you’re NOT reading for the story. You’re not looking at the overall picture–you’re zooming in on the nitty gritty, the small stuff. You’re looking at sentence-level issues and that CTRL F key is going to get a lot of use.

This process may seem overwhelming, but there are specific things to look for that will improve the quality of your writing almost immediately. First, let’s start with the easy stuff–consistency!

Consistency in this case isn’t about the story at all; it’s about the way you have told the story. Is your capitalization and italics usage the same throughout? Here’s a quick reminder of the rules for both.

Capitalization

You use capital letters in the following situations:

- The start of a sentence

- She said there would be no tests on this.

- A title/position followed by a name

- I was joined at the table by Captain Blythe and Admiral Ackbar and prepared myself for some very awkward dinner conversation.

- A nickname or name that you call someone

- Was Mom ever going to show up to this event?

- Was my mom ever going to show up?

- I know Little Bit was thrilled to wear her new dress tonight.

You do NOT use capital letters in the following situations:

- Between dialogue and speaker tag

- “Would you prefer soup or salad?” he asked.

- “I’ll take the salad,” she replied, “with ranch dressing.”

- A title/position without a name

- I enjoyed the commander’s company at the event.

- The president was happy to speak to Admiral Ackbar about the plans for reconstruction.

- A term of endearment

- What do you think, sweetheart?

- I’ll get you, my pretty, and your little dog too!

I realize that last one may be confusing, so let me pause and give some more context. Yes, this means you have to distinguish between a nickname and a term of endearment. I call my daughter Biscuit so often that it’s become a nickname, so I capitalize it. I sometimes call my husband boo, but it’s not something I use every time, so it’s lowercase. You have to decide how you are using it, and then use CTRL F to find every occasion and make sure you have it the same way.

Here’s a handy list of other words you may want to CTRL F to doublecheck capitalization: mom, dad, captain, commander, president, king, queen, princess, prince, detective, sergeant, lieutenant (basically, any titles or positions that come up in your story!)

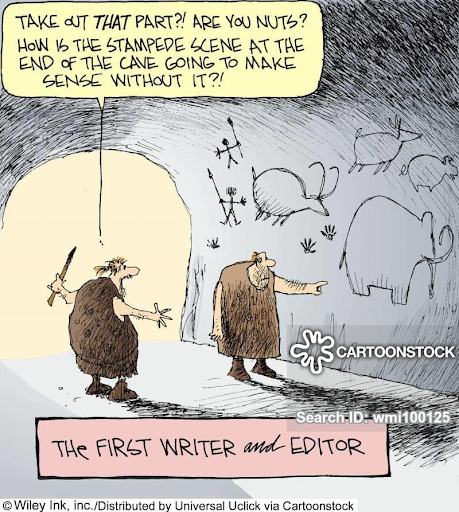

Since we’re here, let me add this suggestion as well–if you have words that are unique to your book, add them to a Style Guide so you can consistently capitalize (or not) or italicize (or not) them throughout the whole story. Does your fantasy world have elves or Elves? Do your characters speak of God or god? Both are correct. Capitalizing something just makes it slightly more formal–heels instead of sandals–so decide if your story needs the elevation.

Final Thought for Capitalization: When in doubt, GOOGLE IT!

Not sure if you should capitalize that dog breed? Google is your friend. Don’t know if you should capitalize Italian food? Google it (Yes, you capitalize food names that are places). What about french fries? Google! (Actually, no because french is the style of cut, not the origin). If you see both, choose the one that fits your situation.

Italics: When to go sideways

Italics have specific uses in many academic style guides, but their uses in fiction are a bit more flexible. Generally speaking, here are some occasions when you should italicize something:

- A flashback or dream sequence

- A foreign word that you want to emphasize is a foreign word

- Jamie calls Claire his sassenach, a word meaning “outlander.”

- Titles of long works like movies, albums, books, TV series (shorter works get quotes)

- Yes, this is MLA format, but I’m an English major! If you’re writing for a discipline, check your style guide, but most fiction uses this.

- I went to see Guardians of the Galaxy 3, and now I can’t stop hearing “Dog Days are Over” by Florence and the Machine.

- Names of planes, trains, ships, paintings

- I took the Orient Express to the Louvre to see the Mona Lisa.

- Sounds

- Thud! We all looked at the door in horror.

- Anything you want to emphasize or draw attention to

- I never said Josh stole the money! Why would you think I meant him?

Again, when in doubt, google it! As long as your usage is consistent throughout your story (and series!), you’re fine.

Take a moment to doublecheck your capitalization and italics usage throughout your story. Then, add any special uses to your Style Guide, you know, that document you have that records details like this so you don’t have to re-read this book before you start writing the next one in the series!

Now, think about other words or phrases that are unique to your story. Make sure that you have spelled them the same way throughout. A useful trick is to CTRL F for easy misspellings of any names or titles that may slip by tired eyes. If my character’s name is Hannah, I check for Hanna, Hanah, Hana, Annah, Anah, and Ana, just in case my fingers slipped, and my spellcheck doesn’t catch it.

You’ve done a chunk of editing for now, and your story is looking much better. Take a breather, and when you’re ready, come back for a final review. Then your story can actually leave the house!