I know that you know this already, but something weird happens to authors when they write their own stories—they suddenly stop following any kind of formatting rules around conversations and just start throwing words and punctuation around like darts in a whirlwind. Writers, you know what dialogue in a novel should look like—I know you do. You’re readers. You’ve all seen this format hundreds of times. But I also know that there is a strange disconnect between seeing how something looks on the page when someone else—a famous author perhaps—does it and applying those same expectations to your own work.

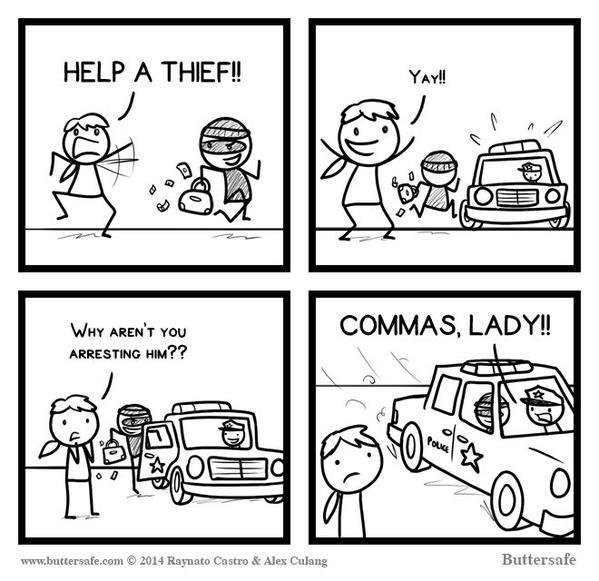

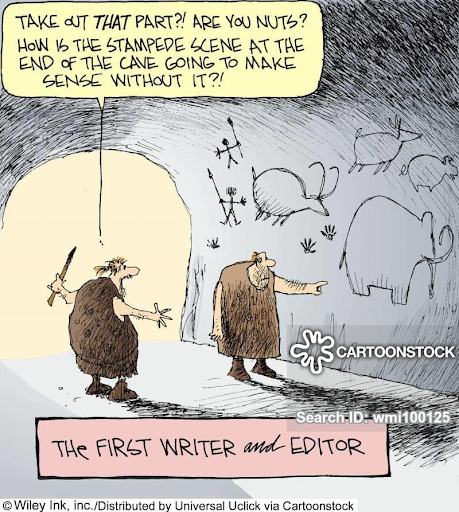

First, let’s talk about why this happens and then get into some guidelines to keep in mind when you are writing dialogue. Sometimes, this disregard for the rules happens for the simplest reason: writers assume someone else will clean up their messy words and formatting. “My editor will fix it for me.” After all, the author is the cook—she need not clean the kitchen as well. Maybe so. But cleaning up after your own words will remind you of the rules—how things ought to look—and you will be a stronger writer as a result. Yes, your editor can clean it up for you, but that person will do so at the expense of everything else, spending valuable time adding commas and lowercasing words instead of getting into the real work of editing. You are essentially paying someone a lot of money to do a menial task when that money could be paying for expert attention on other matters that would make your story better—not just bring it up to code.

Another reason formatting may get wonky is because writers promise they will go back and fix it later—and then don’t actually go back and fix it. I know how it is. We writers may be a forgetful lot. We focus on other things, get sidetracked by other stories, fascinating characters yearning to break free, and we move on to the next one, never actually going back in and checking the capitalization in chapter two. Now, I know you love re-reading your stories. You wouldn’t have written it if you didn’t enjoy reading it (unless you’re writing to market or ghostwriting or something like that, but this blog isn’t for you, specifically). Read it again—except this time pay attention to your dialogue and tweak any remaining issues.

This brings us to another reason for messy dialogue format: you’re just not sure. And that’s okay! Just ask. Or review the guidelines listed below.

How to properly format dialogue in novel writing

- Every time a new person speaks, indent on a new line:

“What are you doing?” Samantha asked.

“Rearranging matches,” Sebastian said, boredom seeping through his voice.

“Why?” Samantha inquired.

“I have no idea,” Sebastian admitted.

- When a character speaks both before and after an interjection, the punctuation should follow like this:

“You never have any idea,” Samantha sneered. “That’s why I’m leaving you.”

“You can’t leave me,” Sebastian replied, “because if you do, who will organize your things?”

- If there is more text beyond the conversation, it can stay in the same paragraph:

Samantha glared at him. “I don’t need anyone to organize my things,” she snapped. “I was just fine in my organizational skills before you came along. I don’t need someone to look after me like a child.” She scanned the library, haughty eyes taking in other annoying details of his obsessive behavior.

“Huh,” Sebastian scoffed. “You couldn’t tell that from where I was standing, dear.” He turned away from his latest project to stare at her. As usual, her clothes were in disarray, her wrinkled pants and untucked shirt almost screaming her need for his guidance. “Come here, Sam. You look a mess.”

“You could use a good mess!” Samantha shouted, stalking out of the library.

- All periods, commas, question marks, and exclamation points go inside the quotation marks.

- You should never put “double” “quotation” “marks” next to one another unless you are making a list of quoted items—otherwise, “double quotation marks” is sufficient.

As I recall, you told me, “I am busy,” “I have plans,” and finally, “I am dead. Please leave a message” the last time we talked about this.

Review the Rules

- If you start a sentence with dialogue, capitalize the first letter of the spoken words but leave the rest in lowercase (except proper names). Put a comma at the end of the spoken words (inside the quotation marks) if it’s not a question or exclamation point.

“I don’t know why you do this to me,” Sebastian pondered. He stared at the books lining the walls, face blank while his thoughts raced. “It’s only matches,” he whispered.

- If you start with the tag (the “he said” part of the sentence), you should start the actual spoken words with a capital letter. Put a comma (if it’s not a question/exclamation) after the verb and before the first quotation mark.

Sebastian said, “She’ll be back.”

- If you interrupt a complete sentence with a tag, do not capitalize the words after the tag. If you have two separate sentences with a tag ending the first one, capitalize the second sentence.

“I know she will forgive me,” he moaned, “eventually.” He glanced at the door, suddenly sure he heard her returning footsteps. “She’s coming back,” he whispered. “I know it.”

- If the spoken words are not a statement, put the question mark or exclamation point inside the quotation mark (as long as the spoken words are a question/exclamation). If the entire sentence is a question or exclamation, then put the marks outside the quotation mark.

“Why do I put up with him?” she wondered, staring down the long hallway. “He’s such a jerk!” she snapped, hands fisting at her sides. “Those matches,” she mused, shaking her head, “make me absolutely crazy.” How dare he say she looked “a mess”? “It’s only matches” indeed!

- Unspoken thoughts should be italicized to distinguish them from spoken words. Consider having tags like “he thought” or “she wondered” so listeners to your audiobook can tell which parts are spoken aloud and which ones are internal thoughts. You don’t need it every single time, but for important moments, it can make things clearer to your listeners.

Just one more box, Sebastian thought, emptying the matches onto the table.

- Only spoken words go inside quotation marks—not reported speech.

I remember when she told me she was leaving me, Sebastian thought, lips pursing as he began lining up the matchsticks. Perhaps I shouldn’t have said, “You look a mess”?

- When quoting someone else’s words inside a quote, use single quotes.

“But why would he say ‘You look a mess’ to me like that?” she wondered, glancing down at her clothing. “I guess I should be glad he didn’t say ‘You look a “hot” mess’ after all.”

- If your character speaks for more than one paragraph (telling a story), don’t use end quotation marks until the character finishes speaking. This means you will not put quotation marks at the end and beginning of each new paragraph.

That’s it! While we’re here, a few things to avoid when dealing with dialogue:

- Do not capitalize the word after the quote unless it’s a proper name: “Don’t do it like this,” She said. (“Do it like this,” she said.)

- Do not put periods between the quote and the speaker: “Don’t do this.” She added. (“Do this instead,” she added).

- Don’t use tag words that don’t actually signify speech: “This is so amazingly funny,” he laughed. Did he laugh those words? No. He laughed after he said those words. “This is so amazingly funny!” He laughed. (I added the exclamation point because he’s probably excited about whatever is so funny, but you could leave the period.) I keep seeing characters who shrug, chuckle, smile, and grin words (and that’s just creepy sometimes). Add the period and separate the words from the action.

I hope this has helped shed some light on how to properly format your dialogue to save both your readers and your editor’s sanity!