Webinar: The Muses on Worldbuilding

Join the Muses for tips on worldbuilding.

Join the Muses for tips on worldbuilding.

One thing to consider when creating the world for your story is the stories the people in your world tell one another about creation. How did your world come to be? What do the people in your world commonly believe about the beginning of it all? Generally, this kind of worldbuilding can be divided into two categories: the truth about creation and the myths about creation. Let’s start with the first part–what actually happened?

To start developing the truth of your world, consider the following questions:

How did your world come into being? Was it formed out of the Void, the result of some cosmic Boom, the plaything of a godlike being? Tolkien’s Middle Earth began as a song of the Ainur, a vision in music that the Valar had to then build based on their understanding and memories of that experience.

Is there just one world/planet? Is it a free-floating ball in space or a disc with an edge that people can fall off? Terry Pratchett’s Discworld is literally a disc on top of four elephants on top of a turtle that swims through space.

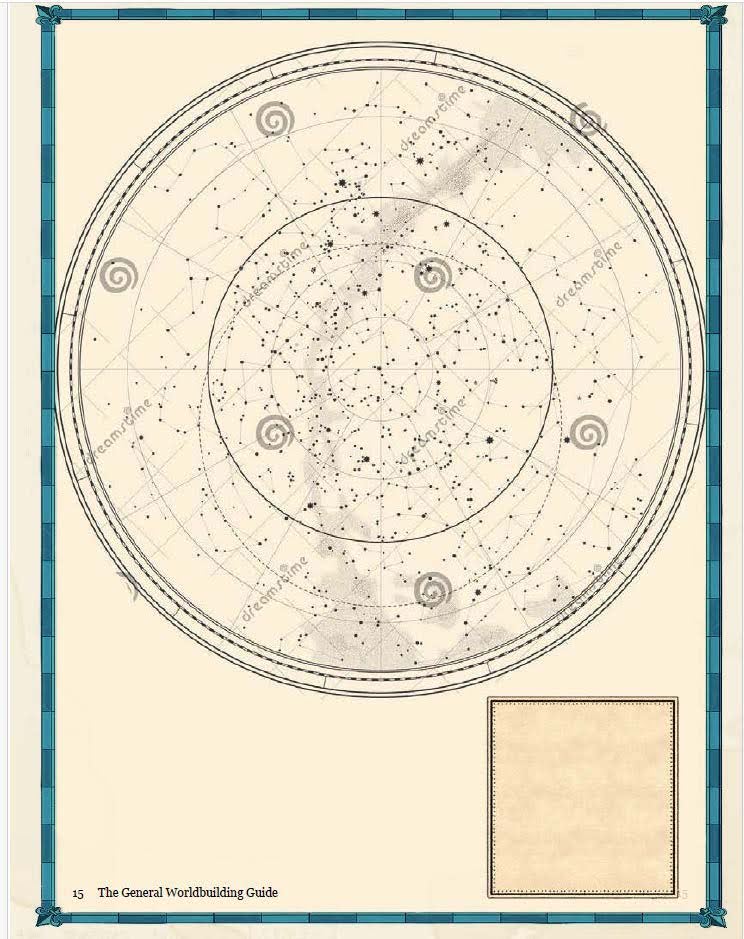

Is the world part of a larger galaxy/universe? Is there a larger cosmos with other solar systems in the galaxy or just the lone world floating in the void by itself? Think about the night sky your inhabitants would see—are those lights in the sky other stars or something else (Shrek’s ogre ancestors, for instance)?

What does the rest of the galaxy/universe look like? Solar systems with planets and suns or black holes or dwarf stars? Titan AE explores a universe where the earth is a tiny piece of a huge tapestry of galaxies.

How big is the universe? Are other worlds nearby or far away? Can people see it or travel to it? How is this done? Get a general sense—if light speed is 186, 282.397 miles per second, how far away is everything from everything else? For example, the sun is 91.4 million miles from Earth while the moon is only 238,900 miles away.

For the people in your world, are there visible stars in the sky? Other planets that can be seen? Do people create constellations from the patterns? What meaning is attributed to these lights in the sky? Is astrology a thing in your world?

Has anyone seen the planet from beyond the surface? Do people travel to space to get that perspective, or do they think the world is flat or ends beyond the mountain range in the distance?

Has the world always looked like this or has it changed over time? Was there an age of dinosaurs and prehistoric plant life or a world covered in oceans, or has it always been as it is now? (This relates to the “how old is your world” question too!).

If it has changed, why? What happened to make it look different? Was this change a result of some natural catastrophe (meteor strike, volcano eruption, ice age, etc.) or the result of the people who live in the world? What did the people do that caused such dramatic shifts in the world? Even earth has had some dramatic environmental shifts over time (*cough* dinosaurs *cough*).

How old is the world? Does the world have an expiration date—like will the sun explode at some point or the gravitational pull let it drift away into the void, or will the world always be there?

If your world is loosely based on the real world, how is it different from the known universe? What world-features are your characters familiar with that readers will recognize? What distinct world-features have you added to distinguish your world from the real one? Do things in the universe have the same name that the scientific community uses (Big Bang, quarks, Jupiter, Io, etc.)?

Bonus Question for Earth-Variants: Is Pluto a planet or a planetoid in your world? How do people argue about this distinction?

Now, think about the second part: What stories do people tell about creation in your world?

How do people explain the creation of the world?Are there competing theories about how it all began? Which ideas will your characters embrace? Which will they deny?

Are there immortals who remember the beginning? How accurate is that recollection (and do they share that knowledge with others)? Will those beings be around for the end of the world, like the robots in AI?

Has the truth of creation been altered in some ways? How? Why? By whom? How does this difference affect the story you will tell in that world?

How much is known by the average person in the world about the creation of the world? Is this knowledge protected or is it shared? How do people share this information (Giver-style or oral culture or what)?

Where would someone go to find creation stories? Are they written down and stored in a library or shared freely among the people? Who is permitted to learn the truth and who is not? Why?

Mythmaking will be the foundation of your world, but it doesn’t need to be the first thing you decide. Let your creative inspiration wander from topic to topic as you wish! Don’t box yourself into getting all of this information carved in stone from the start. One of the great things about being an author is the ability to shift things as you need–creation stories can change as your story develops. You don’t need to know everything from the start. That said, you should have some inkling of these answers somewhere in the back of your mind. Stories that take place in worlds with solid backgrounds, even if those details aren’t known by readers, tend to satisfy in a way that others do not. Readers can sense a solid foundation beneath the plot, details available should the need arise to start digging.

Shameless Self-Promotion Time: Did you enjoy these kinds of questions? Check out more in The General Worldbuilding Guide, available wherever books are sold!

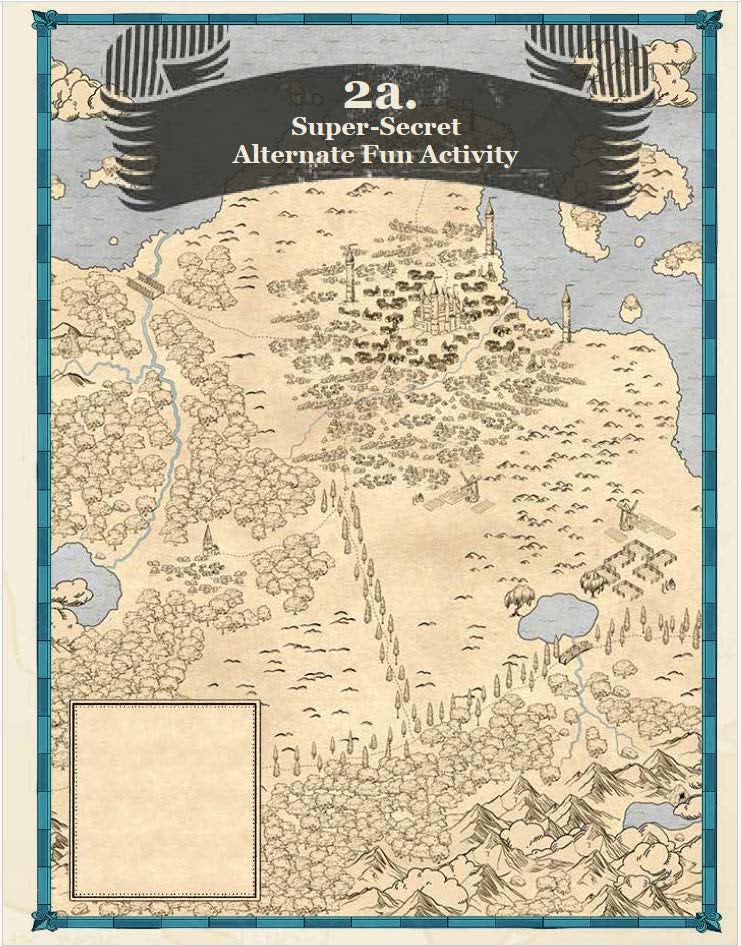

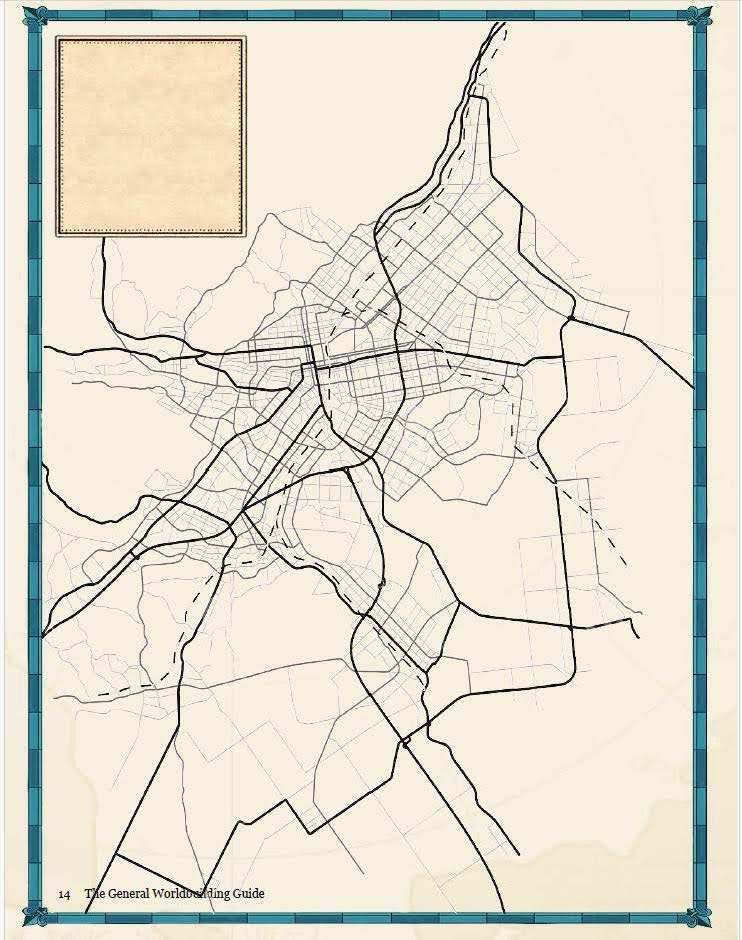

Readers love maps. It doesn’t matter if you’re writing fantasy, thriller, or romance, whether your story takes place in the real world, your version of the real world, or a completely invented world. Readers enjoy pinpointing locations on a map and visualizing the spaces between events and locations. Taking the time to create one is general worth it–both for your readers and for you as the author.

Maps keep you honest and lock in your world details–if the hero’s apartment is at Point A and the murder occurs at Point B and you said those points are 30 minutes apart in book one, having it visualized on a map helps you maintain that distance for the other books in the series.

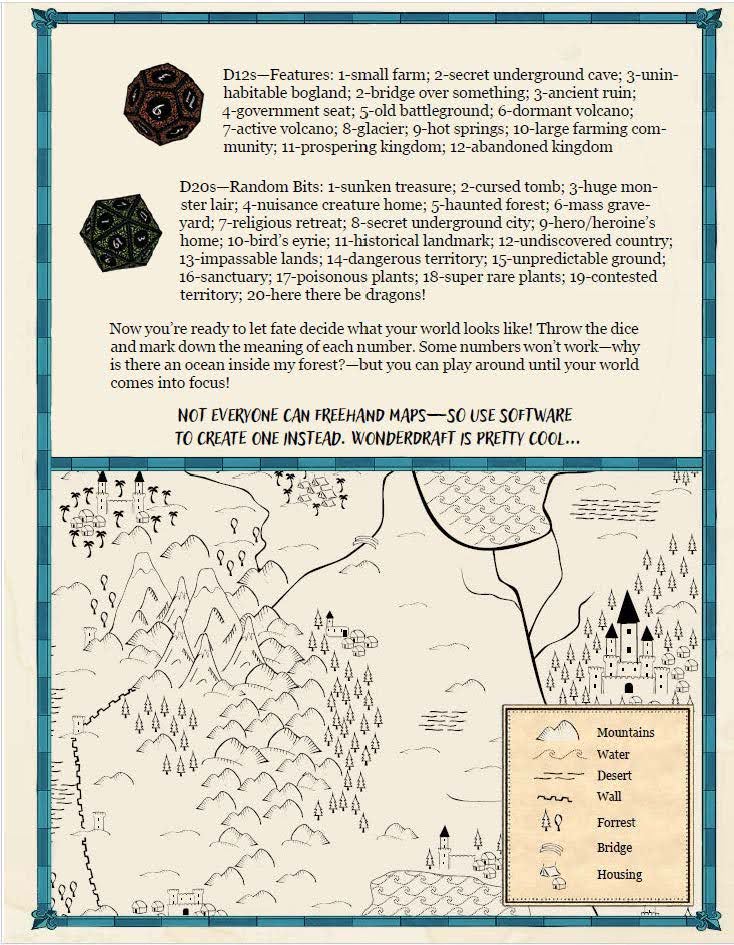

There are plenty of ways to create a map. Many apps will do it for you if you aren’t artistically talented (I really like Wonderdraft!).

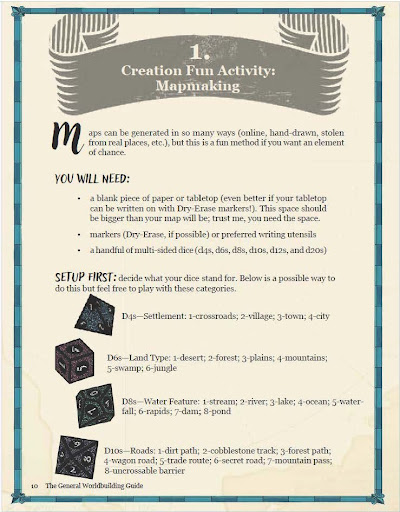

If you want a more old-school approach to mapmaking–with a dash of roleplaying games and fate–consider the following method:

Shameless Self-Promotion Time: Did you enjoy these kinds of activities? Check out more in The General Worldbuilding Guide, available wherever books are sold!

I’m frequently asked how I came up with the Lizardville Ghost Story series idea. The answer is simple: I lived it, well, sort of.

I’m grateful to my mom and dad for buying the damkeeper’s house in 1969. I grew up in Mill Hall, Pennsylvania. We lived on Lizardville Road in a historic four-story home built in the early 1900s, complete with a full basement, first floor, second floor, and a spacious attic.

Our house was nestled in a valley surrounded by mountains. Across the way, we had the ruins of a dam and the remnants of the Axe Factory along Fishing Creek. As kids in a small town of just a thousand people, we often thought life was boring. So, we made the best of it. But now, as an adult, I realize how fortunate I was to grow up in such a close-knit community.

I want to thank my older brother and a small group of neighbor kids—though I use the term “neighbors” loosely since most houses were a quarter mile apart or further. We would walk or ride bikes to visit each other. That was our only way to spend time together. We loved fishing, camping, and hiking in the woods. We used our imagination, or at least I did. Growing up in the seventies was a different experience than what the children of today face. Many of my childhood memories inspired the stories I write.

About half a mile from our house was a motorcycle shop. Back then, motorcycles were shipped in wooden crates lined with large pieces of Styrofoam, and the shop would pile all the foam out back. We would drag these large pieces of foam to Fishing Creek during the summer and float down the river, turning simple summer days into memorable adventures. We would spend a lot of time on the creek swimming and fishing.

Wildlife thrived in the woods, creek, and the dried-up lake bed where the dam once held back the water. From swimming in the creek to fishing and encounters with various animals, these experiences became the foundation for many of my stories. I often get asked if the scene on the bridge was real. Yes, it was, and you will find many of our adventures in The Camping Trip were real, except for me talking to ghosts.

The remains of the Axe Factory, mostly destroyed in a flood before my time, provided a fascinating area to explore. People often ask if we ever had any ghostly encounters as kids. I have to say no, but there were unexplained occurrences that left us puzzled. Our parents or older kids usually say animals or other explanations caused these events.

I encountered all sorts of wildlife in the woods—snakes, muskrats, beavers, deer, and even the occasional black bear. No matter the season, I loved the outdoors. As we became teenagers, our adventures evolved from overnight trips to full weekend excursions. Learning to live off the land was a part of life. We spent more time outside than inside. I look back now and think, what were my parents thinking. But I must mention that times were different back then.

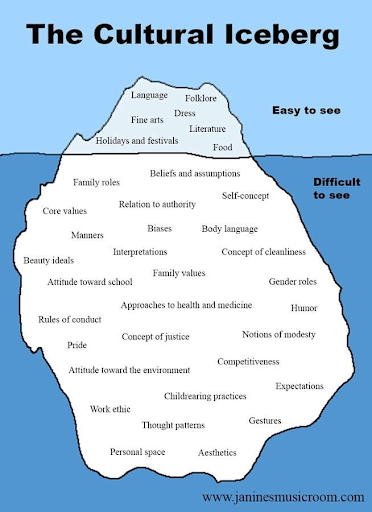

Thinking about the way different people behave is an integral part of worldbuilding. Often it impacts your story, but sometimes, it’s just background that gives readers the feeling that there is a lot more below the water’s surface–that the iceberg is indeed quite deep. One way to do that is to flesh out small details as well as the big picture ideas.

When it’s time to build the cultural practices of the people in your world, consider the following questions:

Considering the answers to some of these questions when you aren’t writing will allow you to continue writing when you reach the moment when you need to insert a detail about one of these beliefs or behaviors or practices. Like thinking this way? Check out The General Worldbuilding Guide for more questions and fun activities!

An often overlooked element in worldbuilding, the weather is more than just background noise. Tiny details here and there–along with a reliable and consistent system–can bridge the gap between a fun read in an interesting world and a fascinating read in a richly developed world that lingers long after the last page is completed.

Here are some questions to consider when planning the weather for your world (and story):

Bonus questions to ponder:

When worldbuilding, a good habit is to create a weather tracker for your world (or at least one location in your world—pick the dominant one in your story). You should know the answers to the following questions without interrupting the writing process: What are the seasons of the year? What is the weather like during those seasons? How will the weather impact your story?

For more Worldbuilding Questions, check out The General Worldbuilding Guide!

Okay, now you have an idea for the world of your story. It’s time to get into it.

Here’s a quick list to keep in mind when building your world:

Shameless Self Promotion: The General Worldbuilding Guide

Okay, let’s get into it with some generalizations.

Worldbuilding is what creative writers do when they form the framework that contains their story. It includes everything from the layout of the furniture in someone’s bedroom and the geography of the city they live in, to the languages spoken by their fellow inhabitants and the technological capabilities of the society that surrounds them. It’s the details that bring a story to life–the thing that separates a decent tale from a life-changing epic adventure that every single one of the reader’s friends must read immediately. It gives a story depth and richness and the sense that there is more beyond the page, that readers could find a pulsing, vibrant existence beyond the edges of the pages they are reading.

J.R.R. Tolkien explains the “magic” of reading in his essay “On Fairy Stories” when he likens what happens to readers who imagine a story to an act of enchantment. The author has written the words, but the readers are ones who transform those markings on a page into scenes in their imaginations. He calls this enchantment an act of subcreation; that is, the readers are “creating” the story for themselves based on the words of the author. This can only happen, he insists, when the world of the story they are reading is believable; in fact, the Secondary World (the world inside the story) must be as believable as the Primary World in which the readers live. A common way to describe what happens when readers engage in this act is the “willing suspension of disbelief.” The idea is that reader willingly suspend their natural disbelief when they enter a story–they know billionaires don’t act like that, or that swords aren’t sentient, or that cars can’t fly, or that word can’t alter the physical world–but for the sake of the story, they “suspend” that “disbelief” long enough to enjoy the story in that world. Tolkien doesn’t like this approach, insisting that if the world is done properly, if the nearly elvish craft of enchantment has been done well, the readers won’t have to suspend their disbelief–they will believe. Fr the time they spend immersed in the pages of that story, they will fall into that world naturally and completely.

How does one accomplish that? According to Tolkien, by having a completely built world in the background of your story. You should know every detail, every crevice, every whisper. That said, Tolkien had reams of journals and maps and lineages and histories for Middle Earth. Do you have to do all that? Of course not. But it should look like you have. After all, unless they read your worldbuilding guide, readers don’t see your entire world anyway–they just see the parts that connect to the story you are telling–but they should believe that the rest of the world is there, the ice beneath the tip of the iceberg hidden beneath the water. If you are confident and consistent in your details, that iceberg will feel massive to readers.

So, how can you provide this magical transformative experience for your readers? Do your homework. Build your world before you step into it (or before you finish stepping out of it on that last page!) so readers feel the world lives beyond the moments they see in the story.

Looking for some help along the way? Check out The General Guide to Worldbuilding and get serious about your world!

Savvy Authors course on worldbuilding. Online 4 week course by JM Paquette

A web course covering worldbuilding, writing tips, and tricks!