Editors can tweak your formatting, but it certainly makes it easier when you do some of the work beforehand—especially for dialogue.

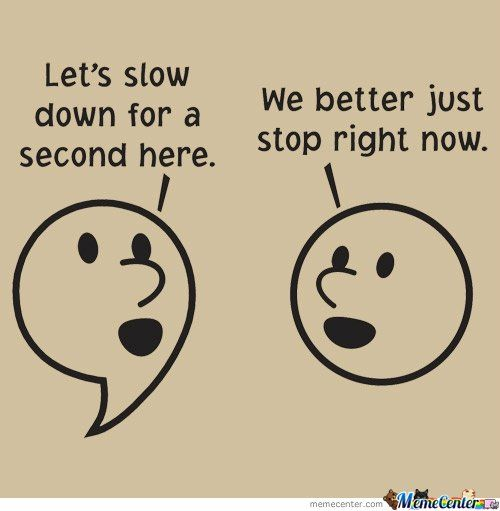

- Every time a new person speaks, indent on a new line:

“What are you doing?” Samantha asked.

“Rearranging matches,” Sebastian said, boredom seeping through his voice.

“Why?” Samantha inquired.

“I have no idea,” Sebastian admitted.

- When a character speaks both before and after an interjection, the punctuation should follow like this:

“You never have any idea,” Samantha sneered. “That’s why I’m leaving you.”

“You can’t leave me,” Sebastian replied, “because if you do, who will organize your things?”

- If there is more text beyond the conversation, it can stay in the same paragraph:

Samantha glared at him. “I don’t need anyone to organize my things,” she snapped. “I was just fine in my organizational skills before you came along. I don’t need someone to look after me like a child.” She scanned the library, haughty eyes taking in other annoying details of his obsessive behavior.

“Huh,” Sebastian scoffed. “You couldn’t tell that from where I was standing, dear.” He turned away from his latest project to stare at her. As usual, her clothes were in disarray, her wrinkled pants and untucked shirt almost screaming her need for his guidance. “Come here, Sam. You look a mess.”

“You could use a good mess!” Samantha shouted, stalking out of the library.

- All periods, commas, question marks, and exclamation points go inside the quotation marks.

- You should never put “double” “quotation” “marks” next to one another unless you are making a list of quoted items—otherwise, “double quotation marks” is sufficient.

- As I recall, you told me, “I am busy,” “I have plans,” and finally, “I am dead. Please leave a message” the last time we talked about this.

Review the Rules

- If you start a sentence with dialogue, capitalize the first letter of the spoken words, but leave the rest in lowercase (except proper names). Put a comma at the end of the spoken words (inside the quotation marks) if it’s not a question or exclamation point.

“I don’t know why you do this to me,” Sebastian pondered. He stared at the books lining the walls, face blank while his thoughts raced. “It’s only matches,” he whispered.

- If you start with the tag line, you should start the actual spoken words with a capital letter. Put a comma (if it’s not a question/exclamation) after the verb and before the first quotation mark.

Sebastian said, “She’ll be back.”

- If you interrupt a complete sentence with a tag, do not capitalize the words after the tag. If you have two separate sentences with a tag ending the first one, capitalize the second sentence.

“I know she will forgive me,” he moaned, “eventually.” He glanced at the door, suddenly sure he heard her returning footsteps. “She’s coming back,” he whispered. “I know it.”

- If the spoken words are not a statement, put the question mark or exclamation point inside the quotation mark (as long as the spoken words are a question/exclamation). If the entire sentence is a question or exclamation, then put the marks outside the quotation mark.

“Why do I put up with him?” she wondered, staring down the long hallway. “He’s such jerk!” she snapped, hands fisting at her sides. “Those matches,” she mused, shaking her head, “make me absolutely crazy.” How dare he say she looked “a mess”? “It’s only matches” indeed!

- Unspoken thoughts should be italicized to distinguish them from spoken words.

Just one more box, Sebastian thought, emptying the matches onto the table.

Let’s get weird for a moment–take a sneak peek at the 4 Horsemen Publications guidelines for formatting weird communication!

A Quick Look at 4HP Standards for different forms of communication

“Normal dialogue looks like this.”

- It should be indented and start a new paragraph every time a different character speaks.

“<If you have characters speaking aloud in a language that is not English/common, but it is shown in English for the readers, use these to show that.>”

- Single quotes with this situation: “<How do you say it? ‘I am tending to her wounds.’>”

- The only time to use single quotes is inside double quotes (a quote within a quote).

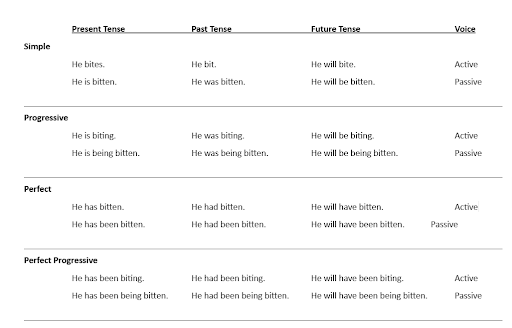

Internal thoughts are italicized and are always in present tense.

<If characters are thinking directly to one another using telepathy, use italics inside these.>

<<If the characters are using non-English telepathy, use italics inside doubles.>>

<If you characters use a non-standard language of communication, just put it inside these.>

- Example: snakes hissing but still communicating; they understand one another.

“If your characters can hear a TV or radio broadcast, use italics inside quotation marks.”

- Phone conversations are treated as normal conversations–no need for italics.

- Sign language is a language–just use quotes to show communication like regular dialogue.

Use italics for foreign words when you want to emphasize their foreign-language-ness.

(Put translations of foreign languages near foreign words inside parentheses like this if you are not using footnotes to translate)

Text messages get left aligned, not indented, like this:

[Name: text message]

[Name: more messages]

Now, it really gets really weird when you have to figure out what punctuation gets italicized and what is left alone… but for now, you have the basics of how to format dialogue!

- Only spoken words go inside quotation marks—not reported speech.

I remember when she told me she was leaving me, Sebastian thought, lips pursing as he began lining up the matchsticks. Perhaps I shouldn’t have said, “You look a mess”?

- When quoting someone else’s words inside a quote, use single quotes.

“But why would he say ‘You look a mess’ to me like that?” she wondered, glancing down at her clothing. “I guess I should be glad he didn’t say ‘You look a “hot” mess’ after all.”

- If your character speaks for more than one paragraph (telling a story), don’t use end quotation marks until they finish speaking. This means you will not put quotation marks at the end and beginning of each new paragraph.