From the Professor’s Desk: Sentence Diagramming 101

Welcome to Sentence Diagramming 101! Here you will find a thorough explanation of English grammar as well as a visual guide through the art of sentence diagramming. This book covers the basics, gives examples, and offers practice exercises, but you will have to visit the accompanying website at sentencediagramming101.com to find the Answer Key and helpful video lectures for each section. Don’t worry–it’s free! No access codes to worry about.

First things first: introductions. You’re probably wondering why you should trust me to teach you all this grammar stuff (and sentences like that probably don’t raise your confidence level)–let me tell you who I am. Here’s my fancy biography:

Dr. Jenifer Paquette teaches English in higher education with her areas of expertise running from the history of the English language and the intricacies of grammatical rules to guidelines for effective writing and communication across disciplines. When she isn’t grading essays or editing manuscripts for academics and creative writers, JM Paquette spends her time writing fantasy and paranormal romance novels. She can be found at 4horsemenpublications.com, on Twitter @authorjmp, and as Author JM Paquette on Facebook and Instagram.

That sounds fabulous, but here’s why I’m really here–I’m a super nerd, and I love words with my soul. I love thinking about how the words in the English language are put together, how we make sense of them, and how they came to be that way in the first place (hint: England got invaded–a lot). I also love the idea of drawing, but I am not talented in that area (or dedicated enough to put in the practice required to improve my skills). Sentence diagramming fills my need to create something moderately artistic, but also basic enough for my wobbly lines (seriously, I’m talking stick figure level of drawing skills). I have left my hand-drawn diagrams out of this book (and learned to use Adobe Illustrator! You’re welcome.), but you should explore your ability to make straight lines of all directions as you work your way through the intricacies of English grammar.

I know that there will be moments where you pause and think, Do I even know any words? We’ve all been there (especially while writing some of the examples in this book!)–and we will get through this together. Even though grammar can seem intimidating and sometimes frustrating, studying how words work can also be rewarding, especially when you see a complicated sentence laid bare like a dissected animal on a science tray. I’ll be honest here–I never enjoyed looking at frog innards as much as I love pulling apart sentences to see how they function (That’s why I was an English major and not a science major!). Come with me on this journey! I promise you will think about language differently.

Sentence Diagramming 101: Fun with Linguistics (and Movies!) is a great resource for anyone interested in understanding the underlying structure of the English language.

“A surprisingly fun jaunt into the convoluted wilds of the English language!”

Sentence Diagramming 101: Fun with Linguistics (and Movies) explores the relationship between words using traditional sentence diagramming and amusing movie references. Inside this textbook, you’ll find detailed explanations as well as 50+ film-focused practice exercises, and on the companion website, you can explore the answer key, informative videos, additional practice, and lively discussions about the English language.

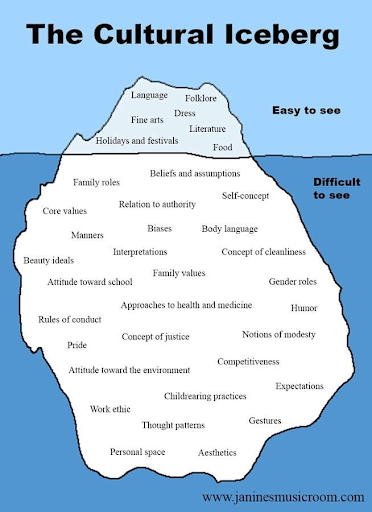

One abiding question often accompanies any discussion of traditional sentence diagramming (Reed & Kellogg): does sentence diagramming create better writers? This book’s answer: Maybe. If you think of the English language as a car, think of this book as a look under the proverbial hood of the language. Someone may know the names of all the parts and how they work together to make the vehicle move when the gas pedal is held down-but does that knowledge create a better driver? Perhaps. Perhaps not. Perhaps that driver will explain spark plugs while they drive straight off a cliff.

Such is also true of writing. English can be messy, filled with archaic bolts and cobbled coils, but somehow, it still manages to get users where they want to go. Hop in and enjoy the ride!

A great primer for writers, word enthusiasts, and those seeking to understand the fundamentals of English grammar, this textbook breaks down complicated ideas into digestible pieces.

Topics include:

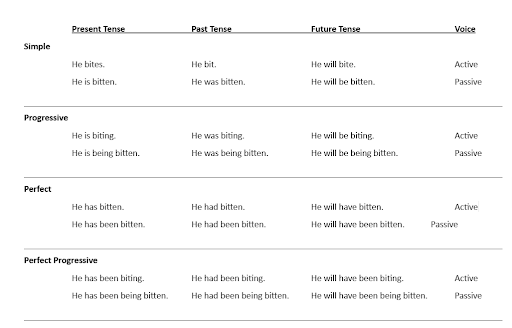

– The Basics: Parts of Speech and Word Function

– Sentence Patterns

– Phrases, Verbals, and Clauses

– Sentence Types

– Weirdness: Questions, Commands, Expletives, Poetry, Made Up and Repeated Words

Additional features:

ADA Compliant

Free Companion Website with Video Overviews, Answer Keys, Practice Explanations, Additional Practice, and Language-Focused Discussions

Get under the hood of the English language with Sentence Diagramming 101!