I am both an author and an editor, and it’s important to know the difference when the time comes to switch roles. I can write my own work. I can edit other people’s work. I can kinda sorta maybe start to edit my own work. But ultimately, I’m never going to see all of my mistakes, so I need another pair of eyes on it if I want it to head into typeset error-free (or as error-free as any other book can possibly be!). That said, there are definitely things I can do to my own work to help the editorial process along.

- Take a break.

Yes, I said it. Walk away from the manuscript. Yes, I wrote it. Yes, I love it. Yes, I wrote it because it’s exactly the kind of book I like to read, but if I want an objective view as I tangle with my sentence structure and word use, I need to have some space (preferably in time, but also in distance, I suppose) between me and when I wrote the book. I’m not saying you need to hide it in a drawer for years, but give yourself a few days to let it settle before approaching it with your prepping-for-editor eyes. If you go directly from composing something to reading it, your eyes will see what you wanted to say, not necessarily what is on the page. Anyone who has written what they considered a semi-passable paper at 4am, printed it out, and then sat in that 8am class staring at a first line that is missing half the words knows what I am talking about. Give your brain a break to see what is actually there.

- Prepare to re-read your book at LEAST twice.

The first time you re-read your book, settle in somewhere comfortable, preferably soft, with a beverage of choice nearby. Your goal during this read-through is to read the book as a reader would. Immerse yourself in the world you created. Meet the characters anew. Make sure that the story goes where you wanted it to go (and tweak all those little annoying story details that no longer make sense now that the story is finished). Don’t stress out about grammar during this read-through. Focus on the story and the details. Gauge the plot, the pacing, the character development, and the dialogue. Appreciate your work as a whole.

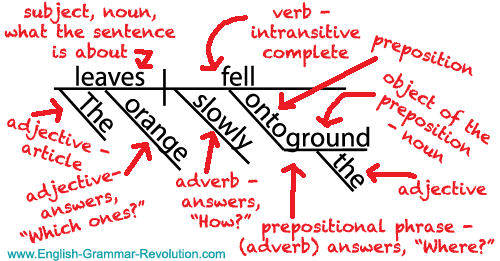

The second time you re-read your book, sit somewhere serious that you associate with work, like a desk or kitchen table. It’s time to read for grammar. That means doublechecking spelling and capitalization. Look for incomplete sentences or phrases that don’t make sense. Check your punctuation, especially around dialogue. Have your reference guides handy during this process (or use google if in doubt). Please do not rely on Word’s editor and even Grammarly. They try heard and mean well, but they are programs that do not know what you are trying to say. They may fix it correctly, but they may make it much worse. Trust your own voice first. And if you aren’t sure, like I said, google it. I guarantee you there is a blog or video about the exact thing you are wondering. If you have an editor friend, ask them (but don’t bombard them unless you plan to pay them for their time–wordsmithing is their job, and unless they spend all weekend asking you questions about your day job, don’t assume their knowledge is free unless they offer it).

- Send it to an editor (or a very helpful beta reader).

I know I already said it, but this is the time to send your book to the editor. You’ve fixed as much as you possibly can, and the rest is for another pair of eyes. That’s fair. Beta readers and proofreaders are your friends at this point if you can’t use an editor. If it’s all on you this time, consult some references. I always recommend Woe is I by Patricia T. O’Conner for grammar questions and Eats, Shoots & Leaves by Lynne Truss for punctuation issues. I can now also recommend 10 Steps to Save Your Editor’s Sanity (available for pre-order from Accomplsihing Innovation Press).

- Read it one more time.

Oh, come on. You’re not sick of it. You love it. Enjoy it one more time and see if anything awkward or weird jumps out at you. Take a moment to appreciate this moment. You created a new story and are ready to release it into the world. You rock.

- Now, start over with a new story!