Editors are not all the same. We focus on different things, specialize in certain areas, and tweak for specific issues. Here’s a brief overview of some varieties of editing.

First, some terms to clarify: proofreading, copyediting, and editing.

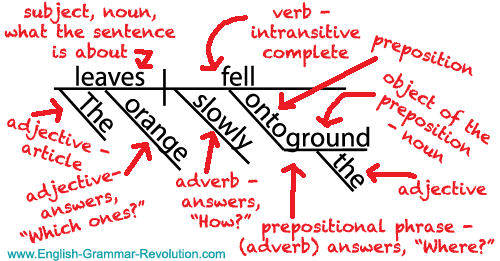

Proofreaders fix surface-level issues to make the sentences grammatically correct (spelling, punctuation, and basic sentence structure—maybe). They do not make your words shiny or impressive or even more effective—they simply bring them up to code. Proofreading typically occurs after your manuscript has been accepted, edited, and even typeset—proofreaders scan for last-minute typos and errors one last time before sending your work out the door to face the public.

Copyeditors and editors generally perform the same service, but pay attention to the title of the service offered. What does the editor call her services? (Note: Copywriters create text for advertisements and marketing materials. Some of them also edit on the side, but copywriting ability does not automatically mean editing skills). They fix the errors in your writing, but they also rework sentences to show their best side to readers. A good editor will whip your prose into shape without losing your narrative voice in the process (it’s still you—but dressed to impress with your perfect hair and shiny smile!).

Editing Levels

Most editors will offer a wide selection of services for a variety of prices. Do some research online to make sure your potential editor is within the suggested price points for services and that you understand what they will be doing for that price point.

- Developmental Editing—This service provides feedback on your idea/outline/concept/really rough draft. This process does not adjust for sentence structure, focusing on the story and world as a whole to evaluate how well it works for readers (so far). This editing should be done before any line editing or copyediting (Why polish sentences that may not make it into the final version?).

- Line Editing—This service focuses on your work line by line, tweaking your words so the sentences are stronger. Most line edits will fix basic grammar in the process (run-on sentences, obvious misspellings), but the focus will be on strengthening each sentence to pack the most punch. Editors will note repeated words and phrases (perhaps sending your document back with all 1147 extra Thats highlighted in yellow), drawing your attention to your bad habits so you can improve as a writer. Editors will smooth tone and narrative pacing in the process, tightening dialogue and cutting out any slack. Editors will comment on confusing scenes (and may or may not fix them for you). If you want to improve your writing style with feedback and tips, line editing is for you. Editors will usually leave comments throughout that promote your growth as a writer.

- Copyediting—This service focuses on grammatical issues, bringing everything up to code (and sometimes above). Copyeditors may provide a style sheet with explanations of common issues for you to review afterward. Copyeditors will also pay attention to continuity—both in story (characters, place, setting, etc.) and format (hyphens, capitalizations, spelling, etc.). If you just want someone to fix your stuff and call it done without much feedback (beyond a style sheet), copyediting is for you.

- Yes, one person can provide both copyediting and line editing—but you have to say that is what you want.

- Format Editing—If you are writing non-fiction or academic work, you may need help with formatting according to specific style guides (MLA, APA, Chicago, etc.). Format editors ensure that your document adheres to the newest requirements for that style. They do not provide feedback on what is said (unless you ask for that—and it’s extra!); the focus is on citations, headings, and some sentence structure issues (APA requires specific tenses in certain situations; MLA has rules for person usage, etc.).

Pricing

Editors charge by the hour or by word count/page. Be clear about which method your editor uses—and what is meant by each one. The Editorial Freelancers association is a great resource when considering standard rates.

For example, I generally charge $10 per page for line editing (my page is roughly 300 words in Times New Roman 12-point font, double-spaced—no quadruple spaces between paragraphs). I look at the entire document and round down (so 96 double-spaced pages/26,936 words would get rounded down for front matter and chapter spaces to 90 pages—$900). To edit the same piece for formatting, assuming the references fill about 12-15 pages—pretty standard for a thesis or some dissertations—it’s much cheaper: only $5 page for APA ($450) or $3 page for MLA ($270). MLA has far fewer restrictions on tense—APA format means I have to read every verb; MLA means I skim for sources and headings.

Because I charge by page and not by time, you know the total cost upfront. Editors who charge by hour may present their fees differently (I would be very careful about expectations here). Note: if you are using an hourly editor, ask what programs they use, if any. I don’t use any automated programs to help me edit (I’m a luddite this way; no judgment—I just don’t like them), so my hourly rates would be much higher than someone who uses a program to help.

It’s critical to lay out your expectations with your editor. Explain exactly what you want and get a description of the provided service in writing.

To finish my example (and shamelessly self-promote), I also accept a deposit upfront ($50-$100) and the rest on delivery. I generally send an email overview with an overall response along with the edited manuscript (I use Word’s Track Changes so you can see everything).

Editors work in different ways—ask how yours operates before agreeing to anything! Communication is key!