Savvy Authors course on worldbuilding. Online 4 week course by JM Paquette

A web course covering worldbuilding, writing tips, and tricks!

Savvy Authors course on worldbuilding. Online 4 week course by JM Paquette

A web course covering worldbuilding, writing tips, and tricks!

I know that you know this already, but something weird happens to authors when they write their own stories—they suddenly stop following any kind of formatting rules around conversations and just start throwing words and punctuation around like darts in a whirlwind. Writers, you know what dialogue in a novel should look like—I know you do. You’re readers. You’ve all seen this format hundreds of times. But I also know that there is a strange disconnect between seeing how something looks on the page when someone else—a famous author perhaps—does it and applying those same expectations to your own work.

First, let’s talk about why this happens and then get into some guidelines to keep in mind when you are writing dialogue. Sometimes, this disregard for the rules happens for the simplest reason: writers assume someone else will clean up their messy words and formatting. “My editor will fix it for me.” After all, the author is the cook—she need not clean the kitchen as well. Maybe so. But cleaning up after your own words will remind you of the rules—how things ought to look—and you will be a stronger writer as a result. Yes, your editor can clean it up for you, but that person will do so at the expense of everything else, spending valuable time adding commas and lowercasing words instead of getting into the real work of editing. You are essentially paying someone a lot of money to do a menial task when that money could be paying for expert attention on other matters that would make your story better—not just bring it up to code.

Another reason formatting may get wonky is because writers promise they will go back and fix it later—and then don’t actually go back and fix it. I know how it is. We writers may be a forgetful lot. We focus on other things, get sidetracked by other stories, fascinating characters yearning to break free, and we move on to the next one, never actually going back in and checking the capitalization in chapter two. Now, I know you love re-reading your stories. You wouldn’t have written it if you didn’t enjoy reading it (unless you’re writing to market or ghostwriting or something like that, but this blog isn’t for you, specifically). Read it again—except this time pay attention to your dialogue and tweak any remaining issues.

This brings us to another reason for messy dialogue format: you’re just not sure. And that’s okay! Just ask. Or review the guidelines listed below.

How to properly format dialogue in novel writing

“What are you doing?” Samantha asked.

“Rearranging matches,” Sebastian said, boredom seeping through his voice.

“Why?” Samantha inquired.

“I have no idea,” Sebastian admitted.

“You never have any idea,” Samantha sneered. “That’s why I’m leaving you.”

“You can’t leave me,” Sebastian replied, “because if you do, who will organize your things?”

Samantha glared at him. “I don’t need anyone to organize my things,” she snapped. “I was just fine in my organizational skills before you came along. I don’t need someone to look after me like a child.” She scanned the library, haughty eyes taking in other annoying details of his obsessive behavior.

“Huh,” Sebastian scoffed. “You couldn’t tell that from where I was standing, dear.” He turned away from his latest project to stare at her. As usual, her clothes were in disarray, her wrinkled pants and untucked shirt almost screaming her need for his guidance. “Come here, Sam. You look a mess.”

“You could use a good mess!” Samantha shouted, stalking out of the library.

As I recall, you told me, “I am busy,” “I have plans,” and finally, “I am dead. Please leave a message” the last time we talked about this.

Review the Rules

“I don’t know why you do this to me,” Sebastian pondered. He stared at the books lining the walls, face blank while his thoughts raced. “It’s only matches,” he whispered.

Sebastian said, “She’ll be back.”

“I know she will forgive me,” he moaned, “eventually.” He glanced at the door, suddenly sure he heard her returning footsteps. “She’s coming back,” he whispered. “I know it.”

“Why do I put up with him?” she wondered, staring down the long hallway. “He’s such a jerk!” she snapped, hands fisting at her sides. “Those matches,” she mused, shaking her head, “make me absolutely crazy.” How dare he say she looked “a mess”? “It’s only matches” indeed!

Just one more box, Sebastian thought, emptying the matches onto the table.

I remember when she told me she was leaving me, Sebastian thought, lips pursing as he began lining up the matchsticks. Perhaps I shouldn’t have said, “You look a mess”?

“But why would he say ‘You look a mess’ to me like that?” she wondered, glancing down at her clothing. “I guess I should be glad he didn’t say ‘You look a “hot” mess’ after all.”

That’s it! While we’re here, a few things to avoid when dealing with dialogue:

I hope this has helped shed some light on how to properly format your dialogue to save both your readers and your editor’s sanity!

Keeping the reader engaged once they hit the end of the story can prove difficult. They came, they saw, they read, and now they are hunting for the next read. Adding value or some means of continuing to sell or hold the reader’s attention after they’ve finished “using” or “reading” your product is a daunting task. Especially since so many of them have TBR, To Be Read, list as tall as they are. What could you possibly do or say at the end of the book that would result in further action from them?

A call to action is a marketing term for inviting your audience to take the next step. This comes in many forms from links, to recommendations, to selling more books or other products. Depending on the author, you’ve seen this from joining a newsletter to checking out the next book in the series. Regardless, this should be easy, hyperlinked, and straight forward. Providing scannable codes and images can go a long way to encourage immediate follow through. Convenience is your friend! Also be mindful to use strong verbs to prompt a sense of urgency and to take action!

They don’t necessarily need to sell anything at all, but there should be some means of securing one of the following intent:

Having them join your newsletter is vital and should be the initial aim for any author. Once you have them on your list, you can continue to engage with them one-on-one. This includes the ability to continually provide a variety of calls to action such as attending live events, vote of book awards, reminders to leave a review and provide exact link to where you wish them, and so much more. It has been proven time and time again that this is the best means for review and preorders on new releases with 10-12% of your subscribers guaranteed to follow through. In short, out of about 100 subscribers, you have the potential to gain roughly 10 reviews and/or sales on the next release!

Invite them to include your book as part of a book club! Including questions in the back of your book often provides a means for libraries and club managers to choose your book over many others. On top of that, providing a means for them to contact you for events or to attend their club meeting, special pricing for bulk orders, or even a link to getting signature plates here can add a more personal touch. On top of that, book club questions can often spark the reader to re-read your book with some of the questions in mind and provide a new reading experience. Check out our blog on creating book club questions: https://4horsemenpublications.com/a-handy-guide-to-book-club-questions/

It’s completely ok to remind readers and encourage them to voluntarily leave a review on their preferred book sites. Even when you send a newsletter using this Call of Action, you will be pleasantly surprised how many new reviews and replies from excited readers come pouring in. Beware of providing direct links to specific retailers, this could cause ebooks and paperbacks to be pulled down. For example, Amazon will unpublish a book that has URLs that aren’t Author specific or Amazon link. A great work around for this is using your author domain, Book2Read, or even LinkTree to limit being flagged.

Again, it’s always a good idea to make sure the reader can connect to you directly. Branding and consistency in how you are posting on social media can keep readers engaged between writing books. It also means you can share the things that inspire you or even cross promote with fellow authors to keep them coming back and being fed the content and stories they enjoy the most. Again, be sure to use the same handle across the board, utilize LinkTree or a website domain to make it convenient for readers to link and follow you via their preferred social media. Not every book genre works on every social media platform, so pay attention to where you readers are coming from!

Lastly, give your readers a sense of security. Let them see the next book in series or a story by you is in the works, or even done. Give them 1-3 chapters of that book and convenient links as to where to go to find it. Again, be cautious not to use direct links from product pages at actual stores such as Amazon, BN, Target, etc. Instead, use this as a chance and teaser to pull in a double Call for Action by combining this with social media and newsletter links. These are ways to continue to reach the reader beyond the initial action of “buying the new/next book” and instead, gives you a chance (and the reader’s permission) to share your author journey, events, books, reviews, and more.

Be creative! Call to Actions come in different formats and there are an amazing variety of articles on how other industries and marketing teams slip them in. Those emails where sections and eye-catching statements have been hyperlinked is another variety. You can think of these as textual precursors to what social media does now, with “link in bio” or even a “click here to watch more” great examples.

Don’t be afraid to get adventurous. These can be blanket statements and should have the punch of those elevator pitches you’ve been playing with for agents. Don’t be afraid to express things about the characters, yourself as the author, or invite them to get something from you through your newsletter.

Click here if you like broody, angsty demons that are legendary!

Mythology, Romance, and all the angst! Oh my! Check out author Valerie Willis.

Want to know the secrets behind the history and lore of the Cedric Series? Click here.

We’ve all been there, right in the middle of a tense scene, when we lose the flow of the writing because we need to figure out a detail, a world mechanic, a backstory, or another little thing that underpins the moment we’re crafting. Worldbuilding is a complicated task, a mixture of Big Picture Overviews and Nitty Gritty Details that require organizational skills and excellent recordkeeping–or I suppose, an impeccable memory, though I cannot claim that (especially after Covid broke my brain!).

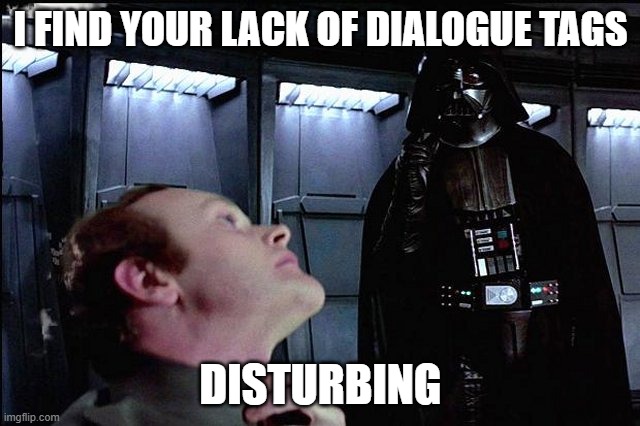

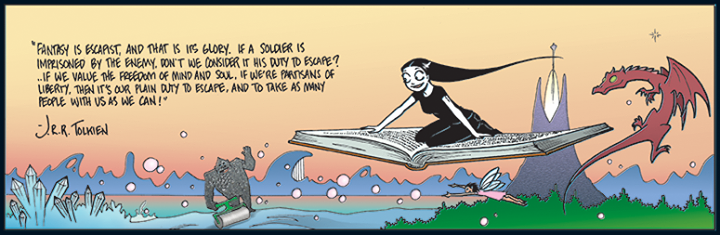

There are many ways to create your world–and there are just as many ways to record those details to doublecheck later on when you need to ensure consistency across a series. Some authors create massive world guides (which they can later publish as reader extras!), though I have seen some people spend so much time on this document that they never actually get around to the story they want to tell inside that world. Another downside of the massive world guide is that some authors get so excited about it that the story they meant to tell gets lost amid the new details and context they have developed. Think of this guide as an iceberg–yes, readers know there’s more under the water. They can explore it if they want when they read your guide (published after the series ends, of course), but remember that your job as the author is to tell a story. With Characters. And Conflicts. All these details are nice to know when the moment arises (so you can mention the former governor’s policies on tea taxes), but they aren’t the story you’re telling–and they should always just stay in the background. Just think–if your story is as popular as Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, you’ll be able to publish multiple guides and early drafts to satisfy the superfans. Most of your readers, though, just want the story that rests atop the world you have created.

On the other hand, some authors wing it, relying on memory and fans to tell them if they switched a detail. Readers tend to be annoyed by this style, but plenty of authors still do it. The downside, of course, is that once a story screws up a detail or world mechanic, it’s really hard to recover–and some readers will DNF and never forget.

Let’s avoid all that unpleasantness and allow readers to get lost in the Secondary World of your story! One way to do this is to get a worldbuilding guide–a book designed to help you create your world. (Psst, I wrote one).

Your worldbuilding guide should help you consider the following:

If you like this layout, check The General Guide to Worldbuilding by JM Paquette (order HERE). This one also includes open-ended questions, guided activities, cool artwork, and a ton of resources like character cards, plot points, general notes, and top five lists.

If you write in a specific genre, you may enjoy the themed Worldbuilding Guides, coming soon from 4 Horsemen Publications–Fantasy, Paranormal Horror, Science Fiction, and Romance.

In the world of storytelling, characters serve as the heart and soul of any narrative. Crafting 3D characters, those who feel real and relatable, requires more than mere description and plot devices. By incorporating psychological principles into character development, writers can breathe life into their creations, resonating deeply with readers and leaving a lasting impact. In this blog post, we’ll explore the significance of using psychological principles to create 3D characters and how it elevates the art of storytelling.

Incorporating psychological principles into character development is an art that elevates storytelling to new heights. Creating 3D characters fosters empathy, authenticity, and growth, leading to more profound connections with readers. As writers harness the power of psychology to craft multi-dimensional characters, they gift their readers with an immersive and transformative journey. So, the next time you sit down to create characters, remember the magic of psychological principles, and let your storytelling prowess shine.

In summary, by understanding the psychological motivations and complexities that drive human behavior, writers can craft characters that resonate with readers on a profound level. Creating 3D characters that are relatable, authentic, and undergo growth throughout the story ensures an engaging and emotionally fulfilling reading experience. As writers embrace the magic of psychological principles, they elevate the art of storytelling to new heights, creating narratives that leave a lasting impact on their audience. So, the next time you sit down to create characters, remember the power of psychology, and let your storytelling prowess shine.

Do you want to learn more?

Check out the book and the course, The Psychology of Character Design—Using Psychological Principles to Design 3D Characters and uncover all the secrets of using psychological principles to craft life-like characters.

We’ve all been there, right in the middle of a tense scene, when something in the story contradicts something we already know about the world, and boom–we’re sitting outside the story again, disappointed and a bit miffed that the author couldn’t maintain the magic. Whether it’s something complicated like a magical system or something simple like the song on the radio at the bar, the stories we read need consistent details to make the world feel believable. These little things all add up to create the word of the story, a world readers to crawl inside and explore.

Tolkien talks about what he called the Primary and Secondary Worlds in his essay “On Faerie Stories” (where he basically defends fantasy as a worthy genre, among other things). The Primary World, of course, is the one in which you live, the one in which you now sit, currently reading these words. Perhaps the words are on your phone screen; maybe you’re waiting for a bus or curled up on a couch, nursing your morning coffee. Either way, odds are you don’t always find the Primary World to be the Best Thing Ever. For Tolkien, the Primary World is good because we all live in it, but it’s definitely lacking in certain aspects–and that’s why readers read Fantasy (or really anything imaginary at all). We want to escape the Primary World and spend some time in a Secondary World.

Now, let’s pause for a moment, as Tolkien did, to examine that word “escape.” One of the easy criticisms of fantasy readers is that they can’t face the real world and have to run away into a book. I’m probably not alone in being told that reading so-called “escapist fiction” is some kind of cop-out, a weakness, a failure to accept the very real world around all of us. Tolkien disagrees, and in the most Tolkien way ever, of course, because he starts by examining that word “escape” (Tolkien’s love of words and philology knows no bounds!). He argues that there is a difference between what he calls the Flight of the Deserter and the Escape of the Prisoner. Readers of fantasy aren’t deserting reality because they can’t handle it. They aren’t running away. Instead, readers (and everyone else in the Primary World) are all prisoners of what can be, honestly, a pretty terrible place sometimes. For Tolkien, a devout Catholic, the Primary World is a fallen world, a kicked-out-of-Paradise world, and so of course, like anyone imprisoned, the inhabitants will long to escape–to occupy their minds with something not so depressing. Keep in mind that Tolkien lived through two World Wars (he fought in WWI and was one of a handful of survivors among his classmates). You don’t need to be Catholic to see that some days, the Primary World sucks–and the urge to escape into somewhere else, anywhere else, is a perfectly normal human reaction. It’s not that fantasy readers can’t handle the real world; it’s that the real world is often ugly and harsh–and humans need a break. A release. An escape. Who would deny a prisoner the chance to escape, at least in the mind?

So where are we prisoners, I mean, readers to escape into? The Secondary World. Where can we find that? Inside the writer’s mind, at first, but then through some artful magic, what Tolkien calls Enchantment, readers are also allowed to inhabit this Secondary World. And this world only works if it is consistent in and of itself. There must be rules, and the rules must be followed, or readers (and prisoners) risk being knocked out of the story forever, unable to enter it believably again.

In other words, if people in the book’s world use the sun and candle rings to tell time, then someone shouldn’t say it’s 10:11pm. If people can fly on broomsticks, then that’s how gravity works (or doesn’t) in that world. The world should be consistent. Readers pay attention to the little things, the details, when they invest in a story. If authors switch out the small stuff, readers will notice, and then remember they are reading a book, finding themselves back in the Primary World rather than still lost in the Secondary World the writer has created for them.

Another thing to keep in mind when discussing worldbuilding: willing suspension of disbelief. You may have heard this term somewhere in a literature course, but the essential idea is this: Of course I always know I’m reading a book. My fingers feel the pages, possibly my neck aches from staying in one position too long, I can hear the soft shuffle of the page as I turn it (or hear that little electric swoosh noise my Kindle makes when I turn on that sound feature). But sometimes, when the enchantment is done right, I can forget all that, and really lose myself in a story, falling headfirst into the world of the characters, blissfully watching their trials as the real world goes by outside the pages. In order to do that, though, I have to willingly suspend my disbelief. If I’m reading a book where people can fly, and I know that flying isn’t possible in the Primary World, I have to willingly and knowingly suspend my natural disbelief in the possibility–and just go with it. Often, people who don’t enjoy reading fiction have a hard time making this leap. In order to travel from the Primary World to the Secondary World, you have to leave your disbelief behind–and accept whatever rules the Secondary World has.

Since we spent so much time on Tolkien, this is a good time to bring up the fact that while he enjoyed plays (and movies) in theory, he never “got lost” in them because he could never forget he was watching people perform either on stage or screen. He thought performers could never transport him the way words on a page could, the way his own imagination could. Either way, there is no transportation at all if the Secondary World isn’t coherent and complete in itself.

Proper worldbuilding, creating a world behind the story that stands on its own and supports the tale being told, is critical if authors want readers to join them in a Secondary World. How does one create a believable world? As the old adage says, lots and lots of time and practice. And maybe a little help.

Check out The General Worldbuilding Guide, coming soon from 4 Horsemen Publications (pre-order HERE).

In Part Two of this blog, I’ll delve into the nitty gritty of worldbuilding, and we can get you started on creating a viable Secondary World for your readers.

You wouldn’t think that three little dots would cause so much trouble… but here we are! An ellipsis is the mark of punctuation created when you join three periods together and hit the spacebar–your writing program should join the separate periods into a single unit of punctuation.

An ellipsis indicates hesitation… and it’s really annoying when people overuse them. There are legitimate reasons for people to pause in your writing (especially during narration), but when someone always ends a sentence with an ellipses, it makes them seem uncertain about everything.

If the ellipses ends the sentence, it looks like this:

If the ellipse is in the middle of sentence, it looks like this:

If the ellipses is in the middle of a sentence where it is more “stuttering” or hesitating, it looks like this:

MORE Ellipses Examples

No Space before—new idea after ellipses…

Space—pause within same idea … within the sentence (Christopher Walken style)

Both space and no space in the same sentence!

The bottom line is that ellipses are hard, but they can be mastered by following a few simple rules. Think about the clauses in your sentence and use that as your guide for spacing!

It’s no secret that having an audiobook for your series is a good idea–albeit an expensive undertaking. When the time comes to have someone narrate your words, creating an audiobook guide (or Audiobook Bible, as we call it at 4 Horsemen Publications) can make all the difference between a performance you are proud of and an experience you don’t want to talk about. You invested a lot of time in writing your story–take a bit more to create a guide that will enable an accurate version of your vision.

An Audiobook Guide is a document you share with your narrator (and perhaps your readers?) that contains two vital pieces of information: how to pronounce the names, places, and specialized vocabulary in your story as well as the mannerisms and speech patterns of your characters. You can do this in a few different ways.

First, let’s talk about pronunciation and why it matters. A lot of authors will say they don’t really care about how a name in their story is pronounced–or my least favorite comment, “Just say it the normal way.” Let’s talk about what the word normal means.

My name is Jenifer. Aside from the odd spelling (only one n–thanks, Dad!), the name Jennifer has been in the top 100 US names for the last few decades. Growing up, I always had at least one (often two three) other Jennifers in my class, meaning we had to pick separate nicknames. For the first fifteen years of my life, I was Jeni (Jenny if I had the traditional spelling). I didn’t think there was any other way to say my name… until I moved to Florida–and my Jeni became the much more serious and adult Jen–and everything shifted.

Instead of Jen, rhymes with “hen” and “pen,” Floridians pronounced my name as “Jin,” like the drink “gin,” rhymes with “sin” and “tin.” I didn’t think I would become an alcoholic beverage, but this simple example shows how much regional variation exists in even so-called “common” name pronunciation. If this kind of thing matters to you as an author (I have shrugged and accepted that my name can sound different in different mouths), and you don’t want your character names mispronounced, take the time to explain how the word should sound, even common names.

There are two ways to describe the proper sounds you want your narrator to use:

Spell the word out the way it would be pronounced with helpful rhymes and references to help the narrator understand what you mean.

The phonetic alphabet (see a basic description here) for all the sounds.

The order in which you list your words is up to you, but think about the ease of use for your narrator. I once had an author hand over an excel spreadsheet with over a thousand words and phrases on it (Thanks, epic fantasy!). At first, this seemed too unwieldy, but it ended up being easier for the narrator to search for keywords and find them quickly.

Another thing that will help your narrator is if you make short recordings of you saying the word. You can do this with your phone and one of the many free voice recording apps. Put these files in a folder that you share with the narrator so they can listen to it over and over again, getting your pronunciation down before they begin reading your story.

After your pronunciation guide, you should also give a quick overview of the personality that influences the speech patterns of each character. Include any accents, verbal tics, famous references (She sounds like Famous Person X in Movie X), or anything else that will help the narrator nail the sound you seek.

Klauden van Sherinak: (Main character) very studious, reserved, patient, speaks thoughtfully except for the rare occasion when he gets upset (usually because Hannah is being a jerk to him). He is a vampire, so if you want to give him an accent different from everyone else (except Hannah–they’re from the same place), go for it.

Hannah van Kreeosk: (Main character) generally happy or excited about whatever is happening, speaks sometimes before thinking (blurts things out), cautious when meeting new people, secretive about her own life/abilities, sometimes shy and awkward, especially around Rory. If Klauden has an accent, give Hannah a similar one, maybe slightly less since she’s been away from home for a bit.

Once you have started your Audiobook Guide, keep it updated as each new book in the series comes out. Just add new names, places, or words from the newest installment. Make this a living document that grows with your series. (Also, keeping it all together makes it easier to remember how you wanted that word from book one to sound when the characters revisit that idea in book five.)

Finding the right voice for your series is a big decision–and there are many other blogs that have useful tips about the process, so I will just sum up the biggest ones here.

Remember that recording an audiobook is expensive. Make sure you and the narrator are on the same page about everything from pronunciation and payments to timeframe and corrections. Listen to the person reading a sample of your work, and think about listening to that same voice for hours as they read your entire story. Listen to other recordings by that narrator and see if you like the vibe.

Choosing the voice for your series is an important decision, and one that sets the tone for the rest of the series. Changing narrators midway can be jarring for readers, so you want to avoid that situation.

Overall, an Audiobook Guide can make life easier for you, your narrator, and ultimately, your readers. You wrote an epic story! It’s time to let new readers hear it–the way you want it to sound.

You may be wondering what is so special about the Oxford comma and why there are so many delightful memes about it. Some context: the comma before the “and” in a list of three or more items is known as the Oxford comma (also known as the serial comma). You may have heard some debate about whether or not this comma is necessary.

Let me assure you—it is.

While it pains the editor in me to say, there are times when a comma doesn’t really matter. You can put it in or leave it out, and the sentence will survive. Readers will comprehend the nuanced meaning, and life will go on. Those commas are often called stylistic commas, and they may rely on their surroundings. Does the previous section or sentence have a lot of commas? Can you get the meaning across without including this one? Then leave it out to spare your reader’s attention span and focus on the important things instead.

The Oxford comma, however—that comma in a list of three or more things—is NEVER a stylistic comma. It is never optional. It means something very specific in a certain situation, and when you need it to be there, you really need it to be there.

Essentially, here’s what the Oxford comma says: these three (or more) items are not related to one another, as in, they are not dependent on the previous item to make sense.

Consider the sentence:

Tonight, at my computer, I drank a cup of tea, a bottle of water, and a can of lime Bubbly.

This sentence has three separate things: tea, water, and Bubbly.

Here’s what happens if I remove the Oxford comma.

Tonight, at my computer, I drank a cup of tea, a bottle of water and a can of lime Bubbly.

Ew. Right now, my cup of “tea” is apparently a mixture of water and lime Bubbly. When you don’t have the Oxford comma, what you are conveying through your punctuation is that the two (or more) items following the commas are EXAMPLES of that first item.

My heroes are my parents, Captain America, and Oprah Winfrey.

Great, you have three heroes: parents, Captain America, and Oprah. Awesome.

My heroes are my parents, Captain America and Oprah Winfrey.

Uhh, really? I didn’t know Cap and Oprah were a thing…

When you leave out the Oxford comma, you change the meaning of the sentence and the relationship between those listed items. Instead of a list, everything after the first becomes an example.

Hence, the litany of glorious memes!

Or you can even argue that the items following the first are being addressed in the sentence!

So, let your readers get the message you’re trying to send. Use the Oxford comma.

Spicy, sweet, steamy, hot, mild, vanilla: All of these are various words used to describe the “heat level” to a romance novel or series. What do they even mean? And in the reviews, readers often leave infamous chili peppers 🌶️ or flames 🔥 to express to one another what “heat level” the romance story hot for them. So what is the heat level?

Heat levels or spice in a romance is often in reference to the sexual content. This implies how often you get a racy scene but as well as how intense, long, or level of description you may be getting out of these intimate rumble in the sheets moments with the characters in a story.

Sometimes we can guess based on the genre and tropes a romance novel has. For example, erotica is going to be an instant heat level of 6 whereas smalltown christian romance is going to be a 1 or 2 max. Dark Mafia? Motorcycle Rebel? Expect 4-6! Rom-com or paranormal romance? Depends on the darkness and can range on averaging 3-5!

As an author, we often struggle to communicate what we wrote and where it falls in this insane system that has developed among readers. So, let’s take a look at what each level looks like from the story or camera angle readers are seeing these lovey dovey or intimately racy moments.

Aww! They’re holding hands, flirting, and at last kissed! Camera can’t follow them through the door.

This is where we get those describers of sweet, wholesome, clean, and more. We also see this as the first time in love stories typically more common in Juvenile Fiction or romance stories for Christian Fiction.

Oh she’s making out with her crush and they’re dating now! Camera can see through the open door before lights out.

Now we are getting to make out and have public displays of affection. Again, we are still in that younger audience, or readers who want the romance vibe without the need to see the naughtier bits. Most authors writing here have a sweeter ambience to their stories and a lot more character development and drama unfolding.

Making out, talking about sex, touchy feely – things are happening. Camera is following them to the bed; clothes are coming off – OH! Lights out!

This is the most common middle ground for a good chunk of authors and books that use romance as a subgenre. We are having some really adult moments, out of wedlock encounters, and talking dirty isn’t off the table. Granted, the naughty bits get rather close and heavy before lights go out and jerk us forward to the next morning and the aftermath of complicated character and plot development that it ties into.

Oh they are going to do this! I see bras and panties. Things are thrown to the floor. The lights are on, but Camera can’t zoom in.

Let’s preheat the oven and let things bake. Now we are taking out time, really showing the body language and chemistry slower and in greater detail. This is your spicy or steamy romance reads who are pulling sexual content more into the plot or as something a character needs to explore themselves or the love interests being presented. We can follow to the bed, but the details are fuzzy and refined. Language and vocabulary may be limited but more daring in comparison to heat level 3.

Camera is in the room, and they are naked and talking dirty. There’s a few explicits and even words like “cock” and “pussy” – WOW!

Now we are in kinky, dark romance, romance erotica, and things skirting at the edge of erotica as a genre. These sometimes will be labeled both in Romance categories as well as Erotica because they have thinned the line between the two. The naughty bits still sit second place or lower as for plot focus, but it’s become a huge element of the story. The vocabulary is vulgar and brash, the scenes daring and if you weren’t fanning yourself before this, you are now. Get ready to sweat, blush, and hide where no one can read over your shoulders more so than ever before.

Camera is there with a whole crew, asking for a leg to move so they can see how things are going into other things. This could be a guide to how to have sex with so many details. Wait, where’d that whip come from?

Unapologetic smut. Sex is the plot and is often a huge part of the world or characters goals, motivations, and conflict. Getting laid varies in many ways, but this is close up, play-by-play, and there’s not much left for the imagination to know exactly where that hand went and what they did once they reached their destination! Fanning and heart thumping, these books are meant to entertain and invoke arousal in the reader themselves much like their visual compadres on the dark, naughty side of the interwebs. That doesn’t mean you can’t find enriching stories, immaculate writing, and amazing character development even with intercourse served as the main course of the plot. Just remember, much like their visual brethren, it’s not recommended to try to reenact what you read.